Feature

Tracing the Meaning of Ever-Circulating Words: Exploring Japanese Aesthetics Through the Lens of “JUNKAN”

Index

“SHIKI”: Capturing the Beauty of Nature Through Words

“MUJŌ”: Fleeting Yet Beautiful

“JUNKAN”: The Ever-Returning Value That Underlies All Thought

We have explored various forms of “JUNKAN” that surround our daily lives — from ecosystems and the role of microorganisms to recycling.

However, one significant question remains: When and how did the word “JUNKAN” come into being, and how did it come to hold its current meaning?

In this final issue, we spoke with dictionary editor Satoru Kaminaga about the origins and evolution of three Japanese words that embody distinct cultural values. These are “SHIKI” (the four seasons), which reflects the ever-changing nature of the environment and climate; ”MUJŌ” (impermanence), which expresses the fleeting and transitory nature of human life; and “JUNKAN” (circulation), which conveys the idea that changing things and events will eventually repeat themselves.

Turning, looping, and returning — why has this concept become so deeply rooted in our values? Let’s embark on a journey through time, tracing the path of words.

“SHIKI”: Capturing the Beauty of Nature Through Words

The concept of the four seasons is deeply intertwined with Japanese culture and values. How did the word “SHIKI” (four seasons) take root in Japan?

Kaminaga

The term “SHIKI” literally refers to the four seasons — spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The idea of dividing the year into seasonal periods can be found in China and other East Asian regions as well. However, how the Japanese have perceived and expressed these four seasons reveals a unique sense of beauty that is distinctly Japanese.

The Japanese sensitivity to the four seasons has been refined through literary works. A quintessential example is the opening passage of The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, written during the Heian period:

“In spring, it is the dawn that is most beautiful. As the light gradually brightens and the mountain ridges become faintly white, thin, purplish clouds stretch delicately across the sky.”

This passage reflects how the Japanese have long observed the subtle transitions of the seasons and expressed them in words with remarkable precision.

So, you’re saying that language has played a key role in nurturing this sensitivity to the seasons?

Kaminaga

Exactly. The Japanese language offers an incredibly diverse range of expressions for describing the seasons. Take cherry blossoms, for example. When fallen petals float downstream, they are called hana-ikada (flower raft). When the blossoms have fallen, leaving only the green leaves, it’s called hazakura (leaf cherry). There are also expressions like hatsu-zakura (early blossoms), hana-akari (blossoms that seem to glow at night), hana-gasumi (blossoms that appear hazy like mist), and nagori no hana (the final lingering blossoms). These rich and nuanced expressions capture the subtle transitions over time.

Such words do more than simply describe phenomena — they reflect the Japanese perspective and sensitivity toward the changing seasons.

In addition, concepts like the nijūshi sekki (the 24 solar terms that describe seasonal shifts) and the go-sekku (the Five Seasonal Festivals — January 7's Jinjitsu, March 3's Jōshi, May 5's Tango, July 7's Tanabata, and September 9's Chōyō) have further enriched the Japanese sense of seasonality.

This sensitivity to capturing fleeting seasonal changes through language is at the heart of Japanese aesthetics.

“MUJŌ”: Fleeting Yet Beautiful

The term “MUJŌ” is known as a concept that embodies Japanese aesthetics. What was its original meaning?

Kaminaga

The term “MUJŌ” refers to the idea that everything in this world is constantly changing and never remains in the same state. In Japan, the use of “MUJŌ” dates back a long way — it already appears in the Man'yōshū, a poetry anthology from the Nara period. In Volume 16, there are two poems titled “Verses on the Impermanence of the World,” which use the concept of “MUJŌ” to express the fleeting nature of human life and the uncertainty of when death may come.

How has the concept of “MUJŌ” evolved throughout the history of Japanese literature?

Kaminaga

During the late Heian to early Kamakura period, Japan saw a shift from an aristocratic society to a warrior-led one, accompanied by growing unrest and heightened anxiety among the people. Amid the spread of mappō thought — the belief that the world was in a state of moral and spiritual decline — the concept of “MUJŌ” became a central theme in literature. The interpretation of “MUJŌ” was further refined through the works of reclusive monks such as Kamo no Chōmei and Yoshida Kenkō. As they observed the impermanence of the world and recorded their thoughts in essays, they elevated “MUJŌ” into an aesthetic consciousness — the idea that things are beautiful precisely because they are fleeting. A striking example can be found in the famous opening passage of Hōjōki:

“The flow of the river never ceases, and yet the water is never the same. The bubbles floating on the surface disappear and form again, never lingering for long. So it is with people and the dwellings they call home.”

Doesn't this passage vividly capture the atmosphere of that era?

So, rather than finding “sorrow” in transience, they discovered “beauty” instead?

Kaminaga

The concept of mujōkan (the awareness of impermanence) greatly influenced not only the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi but also Japanese culture as a whole. Wabi refers to the beauty found in simplicity and austerity, while sabi describes the beauty in the aged, weathered, and withered. Underlying these concepts is the mujōkan-inspired belief that true beauty lies not in brilliance or perfection, but in the incomplete, the fleeting, and the transient.

This aesthetic evolved further under the influence of tea ceremony and Zen Buddhism. It can be seen in the minimalist spaces of tea rooms, the dry landscapes of karesansui gardens, and the appreciation of irregularities or imperfections in pottery — all of which embody the wabi-sabi spirit.

There’s also a Japanese term, teinen, which reflects this worldview. Unlike the common understanding of “giving up” as resignation, teinen refers to achieving a state of acceptance — a deeper recognition of reality. This sensitivity to the transient nature of life, along with the quiet sorrow for what has passed, remains a powerful and recurring theme in Japanese literature even today.

“JUNKAN”: The Ever-Returning Value That Underlies All Thought

With that in mind, I’d like to ask about the term “junkan” (circulation). What are the origins of this word?

Kaminaga

The term “JUNKAN” (circulation) is used in various contexts today — from blood flow and ecosystems to recycling — but its original meaning is “to go round and return to the starting point.”

The character jun (循) means “to follow” or “to go along with,” while kan (環) refers to a circular loop or ring. Together, they describe something that continuously revolves like a jade bead rolling in a circle — never breaking and eventually returning to its origin.

The term “JUNKAN” originates from Chinese literature. It appears in Bai Shi Wen Ji (The Collected Works of Bai Juyi), a Tang dynasty poet. In his farewell poem “Zeng Bie Yang Yingshi, Lu Kezhou, Yin Yaofan” (Farewell to Yang Yingshi, Lu Kezhou, and Yin Yaofan), Bai Juyi used the term “JUNKAN” to express the unending waves of sorrow that follow a parting.

●離憂繞心曲 宛転如循環

(Riyū shinkyoku o meguri, enten toshite junkan no gotoshi)

The grief of parting coils around my heart, revolving ceaselessly like circulation itself.

In Japan, the earliest recorded use of “JUNKAN” appears in Kanke Bunsō, a collection of Chinese-style poems by Sugawara no Michizane from the Heian period. In the poem titled “Ode on Fallen Leaves and Empty Branches in the Garden,” “JUNKAN” is also used to describe an emotional state:

●分任循環運、年如転轂衝

(Bunin junkan shite meguru, toshi wa kokushō o marobasu ga gotoshi)

Duties are cyclical, turning and returning like the spinning axle of a wheel.

In both cases, “JUNKAN” conveys a sense of continuous movement — emotions, roles, or time itself endlessly revolving and ultimately returning to where they began.

So originally, the term didn’t describe physical movement, but rather the flow of emotions or abstract concepts?

Kaminaga

For instance, there’s a dictionary called the Nippo Jisho, published in the early Edo period. This was a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary created by Christian missionaries to help them learn Japanese. In this dictionary, “JUNKAN” (written as jun'kwan at the time) is explained in Portuguese as meaning “the rotation of the heavens” or “the free movement of blood through the body’s vessels.”

While the exact process of how “JUNKAN” came to describe physical movement is unclear, it’s certain that by the Edo period, this usage had become established.

The words “SHIKI” (the four seasons) and “MUJŌ” (impermanence) also seem to share the themes of “change” and “repetition.” Although “JUNKAN” is originally a Chinese term, would you say it has influenced Japanese culture and values as well?

Kaminaga

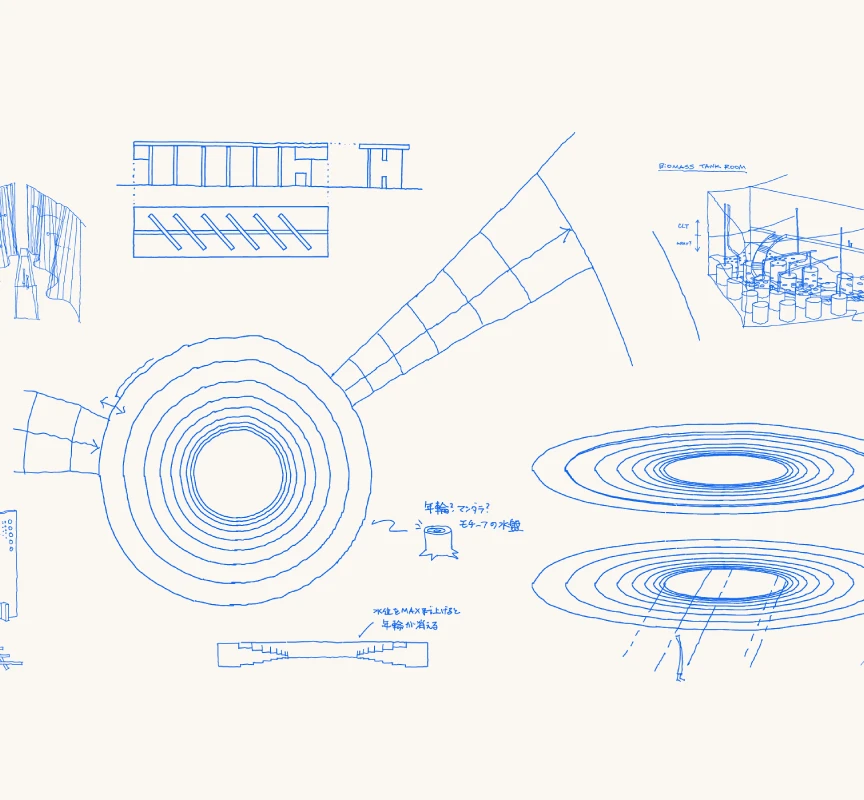

Absolutely. “JUNKAN” plays an important role in Japanese culture as well. For example, Japanese gardens are often designed to create a sense of “JUNKAN” — with flowing water or guiding visitors’ gaze along a circular path. Strolling gardens (kaiyū-shiki teien) are a prime example, where visitors follow a winding path that reveals different scenic views along the way.

In the tea ceremony, there’s also significance in the “JUNKAN” of the tea bowl between the host and guests. Sharing tea from the same bowl is seen as fostering a sense of connection and unity. Although the interpretation of “JUNKAN” has evolved over time, it remains a concept that resonates deeply with Japanese values and aesthetics.

Thank you very much for your time.

Kaminaga

From the rich perspective on the four seasons, born from life deeply intertwined with Japan’s natural rhythms, to the aesthetic of “MUJŌ” — finding beauty in the fleeting and transient — these cultural foundations seem to have nurtured the value of “JUNKAN”, the belief that what moves will eventually return to its starting point. Today, the concept of a “circular society” is being embraced not only in Japan but across the world. The term “circular” is increasingly seen as a guiding principle, evolving to take on new meanings and significance. Perhaps the word “JUNKAN” itself is being called upon to adapt and expand as it journeys forward in time.

Satoru Kaminaga

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1956. After joining Shogakukan's affiliate Shogaku Tosho in 1980, he transferred to Shogakukan in 1993, spending nearly 37 years dedicated to dictionary editing. He contributed to works such as The Great Japanese Dictionary (Second Edition), The Contemporary Japanese Dictionary, and The Dictionary of Beautiful Japanese. Even after retiring from Shogakukan in 2017, he continued working on The Great Japanese Dictionary (Third Edition). His publications include The Troublesome Japanese Dictionary, The Even More Troublesome Japanese Dictionary, and 101 Beautiful Japanese Words Chosen by a Dictionary Editor.

Let’s Share!

How did the word “JUNKAN” become linked to Japanese aesthetics? Share your Monthly JP pavilion and circulate your thoughts.