Feature

Designing Homes with Their “Eventual Disposal” in Mind: Learning from an Architect with a Decomposer’s Perspective on Circularity

Index

Learning About Circulation Through the Life Within a Compost System

Designing Homes Through the Eyes of a “Decomposer”

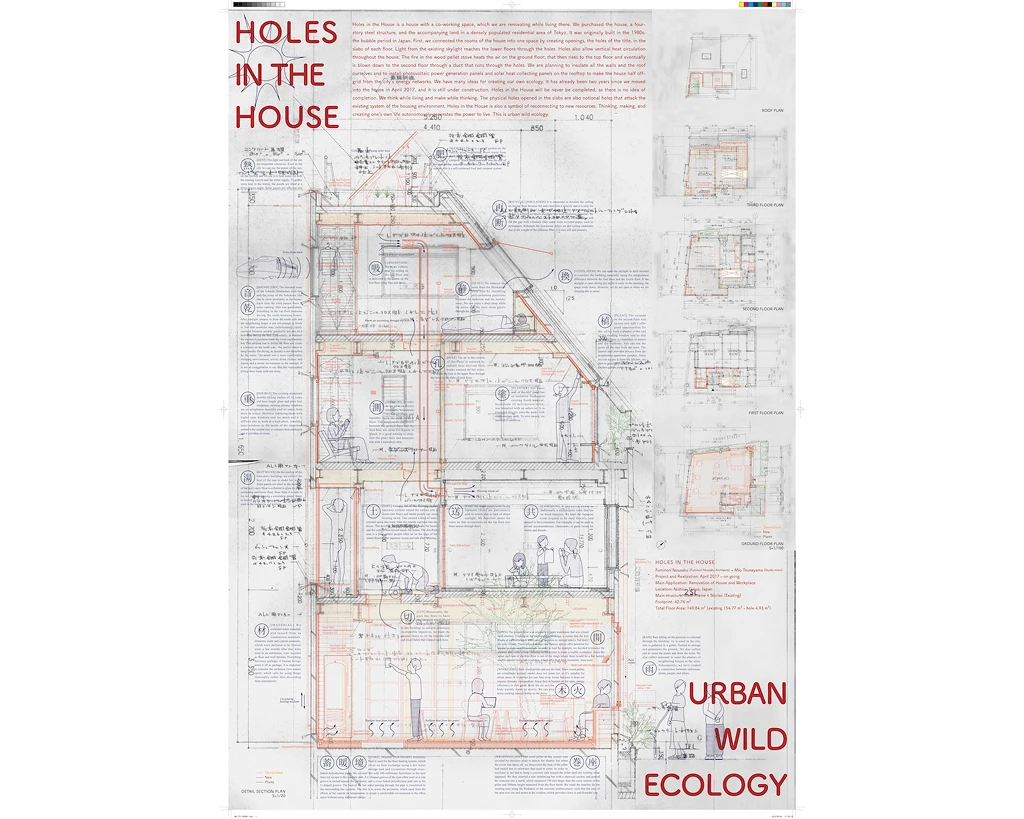

Building a Circular Home with Our Own Hands: Holes in the House

A Circular Society Begins by Seeing “Unwanted Things” as Allies

When considering the transition to a circular society, “housing” is a crucial factor. The process of rebuilding or demolishing homes generates an enormous amount of waste. Ideally, homes should be cherished and passed down through generations, even as occupants change. However, in Japan, new detached houses are often preferred over older ones, unlike in many Western countries. While the number of young people purchasing second-hand homes has been rising in recent years, the market for pre-owned houses is still underdeveloped. Additionally, many municipalities face challenges in dealing with vacant homes left unoccupied after their owners pass away. Amid these circumstances, innovative approaches are emerging to reduce housing-related waste from a different perspective.

In a residential neighborhood in Shinagawa, Tokyo, a striking yellow building catches the eye. This is Holes in the House, the home and office of architects Fuminori Nousaku and Mio Tsuneyama. Originally a second-hand house, it has been transformed through an extensive renovation into a hybrid space combining an architectural office, guest rooms, and a residence.

At first glance, this may seem like a typical renovation project, but it is far from ordinary. What makes it remarkable is that it was designed with its eventual disposal in mind. However, this concept is not a negative one. Instead, the architects have actively incorporated reused materials throughout the building to contribute to the cycle of reuse. At the heart of their approach is a philosophy they call “Urban Wild Ecology,” which provides valuable insights into realizing a truly circular society.

Learning About Circulation Through the Life Within a Compost System

What exactly is the vision behind Urban Wild Ecology? We spoke with one of its proponents, Fuminori Nousaku, to learn more.

“The term 'urban' refers to artificial environments, while 'wild' represents untouched, natural states. The goal of Urban Wild Ecology is to take a step back from overly artificial surroundings and create spaces that coexist with the power of ecosystems and the untamed forces of nature.”

Nousaku, who speaks passionately about Urban Wild Ecology, has installed a compost system near his office as part of this philosophy. Inside, worms and microorganisms thrive, creating a small ecosystem of their own.

“When food scraps are placed in the compost, worms and microorganisms consume and break them down, producing waste. That waste is further decomposed by microorganisms, turning into nutrient-rich compost. What society considers waste can actually be repurposed and integrated into a system of coexistence—this is my vision of a circular society.

These days, the idea of a circular society is often framed as something fashionable. However, I believe that true ecology reveals itself when we embrace the ‘dirty’ realities within compost systems—an ecosystem that is not necessarily clean or beautiful but is fundamental to the cycle of life.”

Designing Homes Through the Eyes of a “Decomposer”

Starting with Holes in the House, Nousaku and Tsuneyama have worked on numerous projects that repurpose discarded materials as valuable resources, including Fudomae House (Tokyo) and Takaoka Guesthouse (Toyama).

“We actively think about circular societies, but our approach feels different from the commonly heard concept of upcycling. Instead, we see ourselves as 'decomposers' within the ecosystem—closer to the worms in a compost system.”

Nousaku likens his role as an architect—incorporating waste materials into new buildings—to the work of worms and microorganisms in compost, breaking down fallen leaves and animal waste to enrich the soil.

The origins of Nousaku’s approach can be traced back to Takaoka Guesthouse in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. Originally a 40-year-old wooden house where his grandmother lived, the building underwent renovations under Nousaku’s design from 2010, gradually transforming over six years into a home, a dining space, and a guest room.

“When designing, I struggled with how to preserve family memories and the town’s landscape. Using brand-new materials wouldn’t retain the essence of the original house, so I repurposed elements like shoji screens and ranma panels. This experience made me realize the importance of preserving old materials and memories. From there, I expanded my perspective, recognizing that buildings, too, are part of the material flow—the cycle of matter. We gather materials, construct a building, and eventually, that building decays and becomes waste. This awareness of material circulation grew stronger within me.”

His commitment to using biodegradable materials in renovations also stems from this consciousness of material flow. Biodegradable materials are those that can be broken down by microorganisms, such as wood and straw.

“Rather than having materials reach the end of their lifecycle as waste, I want to use materials that will eventually return to the earth. This mindset makes me more selective in material choices, often leading me to plant-based materials. Even when designing new buildings, I now prioritize soil-conscious environments and the integration of biodegradable materials.”

Building a Circular Home with Our Own Hands: Holes in the House

In January 2024, Nousaku and Tsuneyama co-authored Urban Wild Ecology (TOTO Publishing). The book serves as a record of the various projects they have worked on, including, of course, Holes in the House.

“The name Holes in the House comes from the vertical opening that runs from the basement to the fourth floor in one corner of the building. This hole allows natural light to pour in from the rooftop window and helps circulate warm air throughout the entire structure.”

Holes in the House also serves as a testing ground, incorporating various ideas for a circular society. The experiences gained here inform other projects, while insights from previous projects are adapted and applied. We asked about some of the sustainable practices being implemented in space.

“We keep costs low by doing as much of the renovation work ourselves. The flooring and wall materials on the first floor were repurposed from scrap cedar and cypress used in an exhibition we participated in. For insulation, we used compressed wood fiber made from wood shavings. When we asked a supplier if they had any discontinued insulation materials, they offered to give them to us for just the shipping cost.

Ordinarily, insulation is made from petroleum-based materials, but that wouldn’t align with our goal of using materials that return to the earth.

The legs of our sofa-side tables are also made from reclaimed wood. Near Mio Tsuneyama’s family home, a row of cherry trees was scheduled to be cut down, so we took some logs before they were incinerated.

There are countless other small details, like using leftover fabric for the staircase handrails and fitting shoji screens onto the windows as interior insulation.”

On the first floor of Holes in the House, a pellet stove reflects Nousaku’s commitment to sustainable choices. Unlike traditional wood-burning stoves, pellet stoves use compressed wood pellets made from sawdust and produce significantly less smoke. Nousaku specifically chose a model that does not require a chimney extending to the roof.

“In terms of pure energy efficiency, air conditioners might be superior to stoves. However, much of the electricity we use daily is generated by burning fossil fuels. When I consider that reality, I feel a certain resistance to relying too heavily on air conditioning. For the same reason, we are also experimenting with self-sustaining energy through solar panels.”

A Circular Society Begins by Seeing “Unwanted Things” as Allies

From simple DIY interior windows to other easy-to-implement ideas, Holes in the House is filled with practical solutions that can be adopted right away. For beginners without DIY experience or architectural knowledge, it offers an accessible starting point.

“We're not doing anything particularly difficult. Everything we do is something anyone can try as long as they have the motivation. We aim to propose ideas that sit somewhere between amateur and expert, making them approachable and practical.”

Nousaku also emphasizes two key points for maintaining momentum in taking action.

“The first is to enjoy the process. Enjoyment is the most important factor in moving things forward.

The second is making time. Without enough time, it's hard to sustain any effort. When you engage in projects like this, you inevitably encounter ‘troublesome things,’ so creating time to deal with them is essential.”

For Nousaku, the most challenging elements are soil and fire. Maintaining soil requires constant weeding and mixing, while the pellet stove demands regular cleaning after every use—tasks that can be quite labor-intensive. At times, he even has to weigh these maintenance duties against his professional work. Still, he consciously makes time to manage them, understanding that these “troublesome things” are essential to a sustainable lifestyle.

“For busy modern people, maintenance-free solutions may seem appealing. However, if we prioritize efficiency too much, we risk losing our ability to create and repair things on our own.

Maintenance isn’t just a tedious chore—it is an act of engaging with and coexisting with the wild.”

“The longer you care for soil and fire, the more you develop an attachment to them—it’s strange how they start to feel like companions. In this perspective, humans are not at the center; rather, soil, plants, and worms are our allies. I believe this mindset is essential for sustaining ecosystems.”

Nousaku envisions a house not as something permanent, but as something that will one day be discarded and reborn into something new. His approach, deeply intertwined with nature, extends beyond architecture and can be applied to all forms of craftsmanship.

It offers an intriguing perspective—one that encourages designing for the continuous circulation of materials and resources, shaping a truly sustainable future.

Fuminori Nousaku

Born in Toyama Prefecture in 1982, Nousaku graduated from Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2005 and completed his master’s degree at the same university in 2007. In 2008, he trained at Njiric+ Arhitecti in Croatia. In 2010, he established Fuminori Nousaku Architectural Design Office. He earned a Ph.D. in Engineering from Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2012 and later served as an assistant professor at the same institution from 2012 to 2018. He then held the position of associate professor at Tokyo Denki University (2018–2021) and Tokyo Metropolitan University (2021–2024). In 2023, he was appointed as a visiting associate professor at Columbia University and a guest professor at the Technical University of Munich. He is currently an associate professor at Tokyo Science University (formerly Tokyo Institute of Technology).

Photo: Shigeta Kobayashi / Top Photo: Ryogo Utatsu