JUNKAN Museum

“JUNKAN”: A Creator’s Vision.

Exploring “JUNKAN” through Varied Perspectives, Ideas, and Expressions.

Thatch Craftsman

Ikuya Sagara

7/11

Thatched Roof Artisan's Artwork: A Great Circle of Sustainability, Inherited from 100 Years Ago and Passed on for 100 Years to Come

Before entering the world of thatching, I was just an ordinary young man with no deep knowledge of traditional Japanese culture. Growing up in the countryside, I was naturally drawn to agriculture and initially aspired to become a farmer. I once read that the word “hyakusho” (a term for farmers in Japan) could be interpreted as “a person with 100 skills necessary for survival,” and I resonated with that idea. One day, while doing a trial part-time job in thatching, my master said to me, “Thatching involves about 10 of those 100 skills. Why don’t you give it a try?” That conversation made me realize that thatching was an extension of the “hyakusho” lifestyle I had envisioned for myself.

Today, I work as a thatched roof artisan based in Ogo-cho, Kita-ku, Kobe City, specializing in re-thatching and restoring thatched roofs. Beyond that, I integrate the materials and techniques of thatching into contemporary architecture and product design, creating expressions that bridge tradition and modernity.

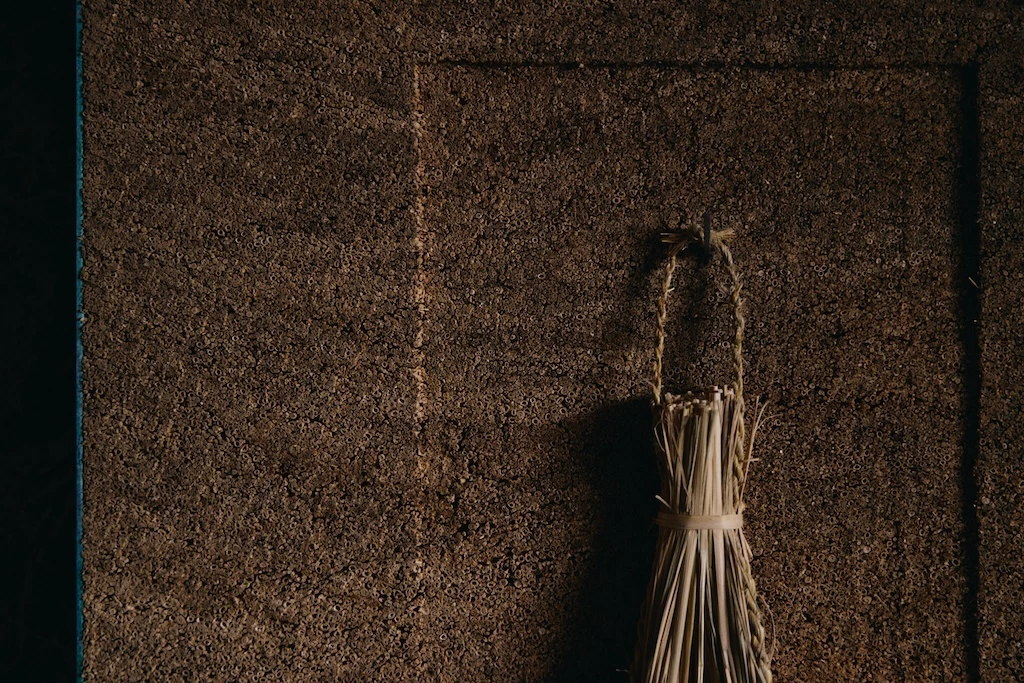

I started creating artworks about two or three years ago when a flower artist approached me with a request: “I need a piece to complement an ikebana arrangement—could you create something using thatching techniques?” That was my first attempt at making an art piece. The artwork was a wall-hanging background crafted from straw, much like a thatched roof. I gathered the straw and cut it smoothly with shears, ensuring a refined surface. Up close, you can appreciate the porous texture of the straw and the subtle shadows created by layering the material at different depths.

Unlike my usual work, where I face massive roofs much larger than myself, creating indoor artworks presented a new challenge. The scale was different, requiring finer finishing and greater density. I had to use smaller shears and pay close attention to detail—an interesting contrast to working on large roofs.

One of the reasons I have been able to continue in this field is that thatching has an inherent lifecycle—"from birth, it already has a promised place to return to." A thatched roof is meant to be maintained and rethatched every 20 to 30 years. The primary materials—susuki (Japanese pampas grass) and rice straw—are harvested and stored in advance. The old thatch removed during rethatching is spread over fields as fertilizer. Even if the house is eventually abandoned, it can be dismantled and returned to its original materials—wood, earth, bamboo, and grass. This traditional architectural system is inherently sustainable, producing no waste. It is a beautifully efficient cycle that minimizes excess while allowing for easy repairs. This approach aligns with Japan’s historical resilience to natural disasters—buildings are designed not only for longevity but also for ease of repair.

The word “circulation” has gained attention in recent years, but it is essential to consider how the cycle is formed. It’s not enough to simply ensure that things “go around.” The quality of the cycle—how smoothly and effectively it functions—is just as important. Instead of discussing sustainability theoretically, I encourage people to observe nature and engage with it physically. Only then can one truly understand how difficult and time-consuming sustainable cycles are. By grasping nature’s generative and regenerative power, we can better estimate the appropriate scale of production and consumption. Self-restraint may sound rigid, but it’s about understanding balance. Recognizing how much we take from nature and how much we return is key to maintaining true sustainability.

One fundamental perspective in understanding circulation is whether a system extends beyond one’s own lifespan. In my craft, we constantly strive to create cycles that span at least 100 years—connecting the past, present, and future. Thatched roofs are passed down from generation to generation, just like the skills required to build them. In this trade, one does not become a true artisan simply by completing their training. True mastery is achieved only when an artisan takes on apprentices and passes down their skills. We must learn from what past artisans left behind while also anticipating the needs of people 100 years from now. How can we take what we’ve inherited and carry it forward into the future? That is the question I continually ask myself as I work.

Photo:Manaya Sakaguchi

Born in 1980, Ikuya Sagara is the representative of Kusakanmuri Co., Ltd. and a thatched roof craftsman. He specializes in the repair and re-thatching of traditional thatched roofs in Kobe, while also exploring modern applications of thatching. In addition, he conducts workshops and seminars to introduce more people to the art of thatching.

Let’s Share!

Do you want to be a part of “JUNKAN” ?

Share your Monthly JP pavilion,

and circulate your thoughts.

Related Artist

1/11

Artist

Miwa Komatsu

2/11

Artist/Plant Director/Doctor (Agriculture)

Mikiko Kamada

3/11

Artist

Hiroki Niimi

4/11

Photographer

Shinichiro Shiraishi

5/11

Artist

Shoji Morinaga

6/11

Plant Dyeing Artist

Misaki Ushiozu

8/11

Artist

Moeko Yamazaki

9/11

Designer / Artist

Sae Honda

10/11

Contemporary Artist

Hanna Saito

11/11

Abstract Painter

Shingo Francis