Feature

A to Z on Japanese Food What Are the Important Elements That Should Be Preserved for Future Generations?

Index

The Evolving Definition of Japanese Food Three Key Points to Understand

The Unspoken Aesthetics of Japanese Food The True Nature of the Aesthetics Essential to Japanese Food

The Evolution of Japanese Food in Response to External Influences What is the Unchanging Core?

Japanese Food Culture Has Been Nurtured Through a Long Cycle We Are Now Consciously Preserving It

In this article, we will introduce key Japanese foods where fermentation plays a crucial role. Recently, Japanese cuisine has gained global recognition for its eco-friendly practices, utilizing all parts of seasonal ingredients. However, defining Japanese food is complex and varies among chefs and researchers. While sushi and tempura are commonly recognized as Japanese dishes, the inclusion of ramen, now considered Japan’s national dish, sparks debate. Moreover, despite the global availability of diverse cuisines in Japan, opportunities to enjoy traditional Japanese food are diminishing. How can we ensure the preservation of this culinary heritage?

We spoke with Mr. Naoyuki Yanagihara, who studied fermented food science at university and now teaches Japanese cuisine at his cooking school. The interview, titled “A to Z on Japanese Food,” also highlights dishes served at Tenoshima, a restaurant Mr. Yanagihara endorses as the best place to experience authentic Japanese cuisine.

Interviewee: Naoyuki Yanagihara

Photos: Tohru Yuasa

─

What is Japanese food? Historically, the term is not as old as French or Chinese cuisine, and its definition remained vague until it was recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. At one point, there was a movement to register Kyoto cuisine as the representative of Japanese food with UNESCO, but this was rejected as it would favor a specific region. After extensive discussions among experts, the definition of Japanese food was eventually narrowed down to three key elements.

The Evolving Definition of Japanese Food

Three Key Points to Understand

The first point is that Japanese cuisine capitalizes on the rich and unique ingredients found in Japan. As an island nation with a long north-south axis and oceans where warm and cold currents collide, Japan boasts a wide variety of fish, with the Toyosu Market consistently offering 150 to 200 varieties. The diversity of vegetables is equally impressive. The concept of “one soup and three dishes” is central to Japanese meals, where three dishes accompany rice and miso soup. These dishes are not categorized as main or side dishes but are an array of items prepared in various ways, such as stewed, baked, steamed, or cooked differently. Typically, about 13 ingredients are used in Japanese food, compared to the average of 7 to 8 kinds used in international cuisine.

The second point is that seasonality is a cornerstone of Japanese cuisine. Since ancient times, and particularly during the Edo period, it has been considered stylish to eat seasonal foods as soon as they become available. Unlike French cuisine, which uses rare and luxurious ingredients like foie gras and caviar, Japanese cuisine focuses on the freshness and seasonality of ingredients. For instance, the first bonito of the season, caught off the coast of Kamakura, can fetch several hundred thousand yen. Similarly, tuna is auctioned at high prices during the New Year due to its seasonal significance.

The third point is that Japanese cuisine is renowned for its healthiness. In Japanese cooking, water is mainly used for making broth, boiling ingredients, and for cooking. Fermented seasonings such as soy sauce, miso, mirin, and vinegar are added to it. Overseas, cooking is done in oil and flavored with spices. So when a dish tastes good, it is often described as having a “good flavor.” Because Japanese cuisine does not use oil, the original flavor of the ingredients becomes more important.

When I explain Japanese food to foreign chefs, they are often surprised and say, “Only Japanese chefs make this kind of food.” Overseas chefs aim to make an impact with bold flavors. For example, in Spain, you can find dishes that are extremely sour from a Japanese point of view, but in their culture, this is considered a positive attribute. On the other hand, Japanese chefs tend to value balance in their dishes. This emphasis on balance likely contributes to the consistently high quality of Japanese restaurants, where the food is delicious no matter which restaurant you visit.

The Unspoken Aesthetics of Japanese Food

The True Nature of the Aesthetics Essential to Japanese Food

However, no matter how much we try to refine the definition of Japanese food, there are still nuances that cannot be verbalized. One such nuance is the Japanese aesthetic sense. For example, are curry and rice or ramen considered Japanese food? Today, Japanese people probably eat these dishes more often than traditional Japanese food. Yet, it feels uncomfortable to label them as Japanese food, even though they are national staples. This distinction is puzzling.

Take the placement of chopsticks, for instance. Most Japanese people would feel uneasy if chopsticks were placed vertically. This discomfort stems from an aesthetic sense. There is an interesting story behind this practice. Chopstick culture was introduced to Japan from China around the time of the Sui dynasty when envoys were sent. At that time, chopsticks were placed horizontally. Later, during the period of the Japanese envoys to the Tang dynasty, the Tang culture placed chopsticks vertically, as they had rejected the previous era’s customs. However, in Japan, the horizontal placement of chopsticks persisted. Thus, something of foreign origin became an integral part of Japanese food culture, giving rise to a unique sense of beauty.

The Evolution of Japanese Food in Response to External Influences

What is the Unchanging Core?

What exactly is the core of Japanese food? It is rice. If we consider that Japanese people prefer dishes that complement rice, even foreign-origin dishes can become part of Japanese cuisine. Take sukiyaki, introduced during the Meiji period, for example. Few would dispute its status as Japanese cuisine today. Similarly, curry, a relatively recent arrival in Japan, may one day be regarded as quintessential Japanese fare, much like sukiyaki.

No aspect of Japanese cuisine has been untouched by foreign influences, not even tempura. Even rice, traced back to its origins, came from outside Japan. Yet Japan possesses a remarkable ability to assimilate foreign elements and imbue them with its own essence, shaping its unique culinary culture. Rather, this process of adaptation and integration is a defining characteristic of Japanese food.

In my cooking school, I refrain from rigidly defining “how Japanese food should be.” Ingredients hail from all corners of the globe, and like chefs of old, I aim to evolve Japanese cuisine by incorporating diverse elements. Japanese cuisine is multifaceted, seamlessly blending ingredients, dishware, and cooking techniques to create a distinct flavor profile. Thus, when presented on a Japanese plate and enjoyed with chopsticks, any dish can take on the mantle of Japanese cuisine. Even if an element seems out of place, there’s always a way to harmonize it.

However, when it comes to seasoning with oil, as common in other cuisines, I find it may stray from the essence of Japanese food. My goal is to accentuate the natural flavors of the ingredients. Furthermore, rice must remain central. While I’m open to adapting accompanying dishes to suit contemporary tastes and circumstances, if rice were to disappear, I fear the soul of Japanese cuisine would vanish with it.

There is no formal school of Japanese cuisine; rather, the tradition has been maintained within households. Simple meals like grilled fish, rice, and miso soup are considered quintessential Japanese dishes. Japanese food enjoyed in restaurants doesn't have to rely on expensive ingredients either. For example, boiling freshly picked spinach, adding roasted sesame seeds, broth, and soy sauce, and serving it on a special plate transforms a basic spinach ohitashi (blanched spinach) into a refined dish through meticulous preparation.

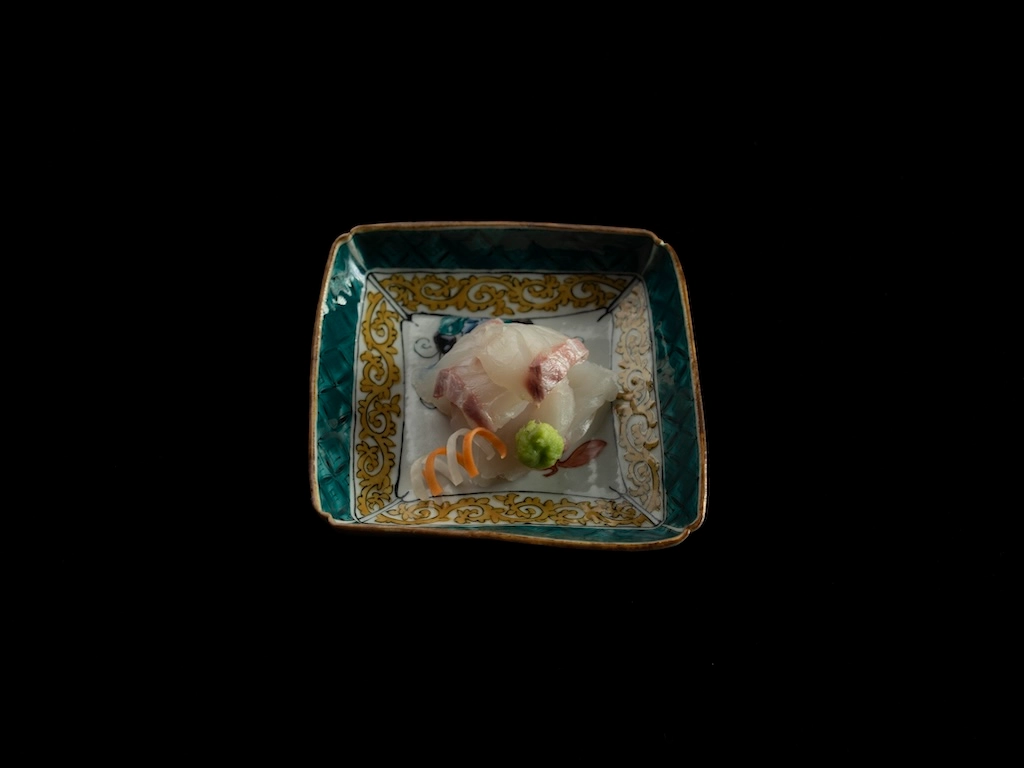

As a recommendation for a Japanese restaurant, I mentioned Tenoshima, run by Ryohei Hayashi, who trained at the esteemed Kikunoi kaiseki restaurant. Tenoshima doesn’t depend on high-end ingredients but instead focuses on proper technique and fair pricing. This approach captures the essential spirit of Japanese cuisine that has been cherished in homes.

Japanese Food Culture Has Been Nurtured Through a Long Cycle

We Are Now Consciously Preserving It

Japan’s cultural history spans over 2000 years, and remarkably, it has never been invaded since its culture began. It is a unique country where culture has continued uninterruptedly under the Emperor system, despite changes in leadership. The Muromachi period saw the birth of the formal beauty of traditional arts like the tea ceremony and flower arrangement, while the Edo period introduced Western culture. During the Meiji Restoration, the Emperor was served a full course of French cuisine. However, each time foreign cultures influenced Japan, they were interpreted in a distinctly Japanese way, a hallmark of Japanese adaptability. This cycle of adaptation has continued in Japanese cuisine as well.

Today, the fusion of global food cultures is accelerating, leading to a homogenization of tastes. For example, Kyoto and Edo cuisines, which traditionally had different preparation methods, are blending. In modern Tokyo, usukuchi (light) soy sauce is commonly used, and it is not unusual to find raw tuna in Kyoto, where fermented fish once dominated.

This trend mirrors the presence of family restaurant chains in rural train stations, where uniformity is becoming the norm. Even when dining on French cuisine, Japanese ingredients are often used. Therefore, establishing a foundation or guidelines for preserving the essence of Japanese cuisine is becoming increasingly important.

Until recently, the term “food culture” was absent from Japanese legal texts. However, a few years ago, it was included in the revised Basic Act on Culture and the Arts. Food culture is fluid, evolving with daily life. Thus, documenting the food culture of each era is crucial, even if it doesn’t remain in its original form. What has been naturally preserved until now must be consciously passed on in the future. I hope the Japanese Pavilion at the EXPO can serve as a catalyst for this effort.

Tenoshima

The restaurant Tenoshima was opened in March 2018 by Ryohei Hayashi, who trained at the renowned ryotei restaurant Kikunoi in Kyoto, and proprietress Sari Hayashi, a graphic designer turned Japanese chef who previously ran a Japanese restaurant in Northern Europe. The restaurant is named after Teshima, a remote island in Kagawa Prefecture, where Hayashi’s original home is located. Emphasizing the concept of “Japanese food for everyone,” Tenoshima was awarded a star in the Michelin Guide Tokyo in 2023.

◉Minami-aoyama 1-55 Building 2F, 1-3-21 Minami-aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo

☎️+81-3-6316-2150

Naoyuki Yanagihara

Born in Tokyo in 1979, Yanagihara studied fermented food science at Tokyo University of Agriculture. He gained experience working for a soy sauce company in Shodoshima and as a kitchen crew member on a Dutch sailing ship. Currently, he teaches Japanese cuisine and cha-kaiseki at Yanagihara Cooking School in Akasaka, Tokyo. Yanagihara has appeared on NHK’s “Kyo no Ryori (Today's Menu)” and other TV programs, and has supervised cooking and historical research for historical dramas. In 2015, he was appointed as a Japan Cultural Envoy by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and in 2018, he was named a Goodwill Ambassador for Japanese Cuisine by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Let’s Share!

Japanese food continues to evolve with influences from abroad.

Share your Monthly JP pavilion and circulate your thoughts.

Related Articles

02/03

Why Is Soy Sauce Good? Exploring Japanese Fermentation Culture Through Seasonings

How did Japan become a fermentation powerhouse? An expert explains the background.

Read more

03/03

The Beauty of Microbial Creation: Welcome to the Museum of Fermented Foods by Kaoru, Founder of Dress the Food

Let's take a peek at the formative beauty of fermented foods from the perspective of food director KAORU.

Read more