Feature

All Living Things Eat and Discharge: The Story of the “Cycle of Life” as Seen in the Food and Excretion of the Natural World

Index

Reasons Why Forests Aren’t Overflowing with Fallen Leaves, Carcasses, and Excrement

The Earth’s Ecosystem: The Connection between “What We Eat” and “What We Excrete”

The Key to Connecting “End” and “Beginning” Lies in Excretion

The cycle of nature revolves around the “cycle of food and excretion” of all living things.

Every organism eats and excretes to survive. This interconnectedness sustains the natural environment. While much attention is given to “eating” in various contexts, “excretion” is rarely discussed. In this exploration of the cycle of life, a topic both familiar and often overlooked, we uncover insights that can guide us toward the future.

Reasons Why Forests Aren’t Overflowing with Fallen Leaves, Carcasses, and Excrement

Imagine entering a forest teeming with diverse life. It is filled with dense trees and fresh air that invites you to take a deep breath. You can sense the rustling of creatures, a stark contrast to the human world we typically inhabit.

As you walk along the path, the ground is covered with fallen leaves and exposed tree roots. The earth feels soft under your feet, unlike the hard, unyielding asphalt. Walking barefoot, you would directly experience its gentle softness.

Naturally, no one is cleaning up the forest. So, why aren’t there piles of animal remains or excrement? Why aren’t the trails overflowing with fallen leaves?

Every day, animals excrete and die, and leaves fall. In the human world, waste and remains are managed by people. In the natural world, this task is handled by microorganisms. Yet, this perspective is centered on human experience. The cycle of nature revolves around the “cycle of food and excretion” of all living things.

The Earth’s Ecosystem: The Connection between “What We Eat” and “What We Excrete”

Living organisms categorize into animals, plants, and fungi.

Among them, animals exhibit diverse forms like lions, dogs, birds, and humans, all engaging in the fundamental activities of “eating” and “excreting.”

Even in the depths of the sea, creatures like tubeworms, which cyclically process hydrogen sulfide through internal bacteria, adhere to this pattern. Despite the intricacy of their behavior, the specifics of their ecological role remain largely unknown. Broadly, animals sustain themselves through this perpetual cycle.

But what about plants and fungi? While plants lack a conventional excretory process, reconsidering “consumption” and “excretion” reveals their involvement in this universal cycle.

Plants harness sunlight, atmospheric carbon dioxide, and water from roots to synthesize sugars via photosynthesis, concurrently releasing oxygen as a byproduct. Thus, the sustenance they derive constitutes their intake, while the surplus oxygen they emit acts as their excretion.

Fungi, on the other hand, subsist by decomposing organic matter like dead trees, fallen leaves, and animal remains. This decomposition liberates carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and inorganic nutrients into the soil. Plants then absorb these fungal excretions as food, taking in inorganic nutrients through their roots and carbon dioxide through their leaves for photosynthesis, which serves as their “diet.” In turn, animals rely on plants for oxygen, generated through photosynthesis.

Thus, the interconnectedness of all life forms revolves around the intricate dynamics of “consumption” and “excretion.”

In modern society, humans seem disconnected from this natural rhythm, often relegating discussions on human waste to the periphery of public discourse.

Our reliance on flush toilets epitomizes this disconnection, as waste is whisked away to treatment facilities. Here, through the activated sludge process*, microorganisms facilitate the breakdown of waste into solid sludge and water, with the latter undergoing filtration, deodorization, and disinfection before discharge into water bodies. Meanwhile, the solid residue is subjected to drying, incineration, or conversion into cement material.

While this engineered system has undoubtedly bolstered hygiene and curbed urban epidemics, it veers away from the innate cycle of “consumption” and “excretion” in nature.

While repurposing waste as fertilizer underscores its utility, such practices primarily serve human interests rather than acknowledging nature’s intrinsic life cycle.

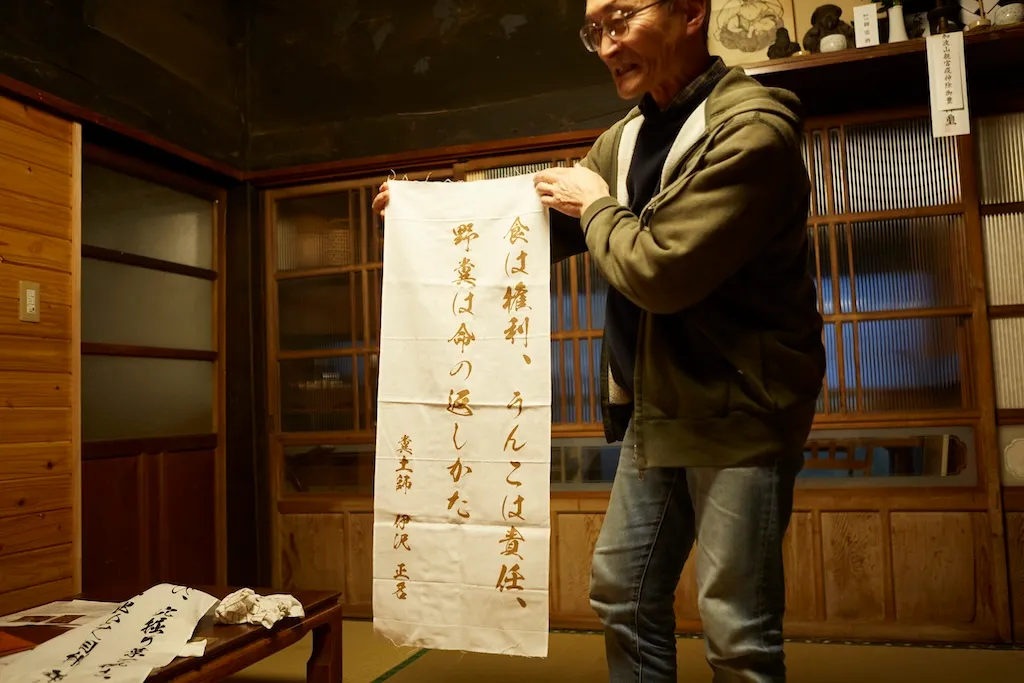

Nonetheless, some individuals like Masana Izawa, self-identified as a “fecal ecologist,” choose to live in harmony with this natural rhythm, recognizing the vitality of the ecosystem’s cyclic dynamics.

*Activated sludge process: Organic matter is treated through alternating aerobic and anaerobic decomposition using microorganisms.

Mr. Izawa has been exploring and practicing the natural cycle of life through the lens of “excretion.” A nature conservationist since 1970, he has been fascinated by the decomposition activities of fungi, documenting this world as a photographer. However, in 1973, upon hearing news of a campaign against human waste treatment plants, he began to contemplate “excretion.”

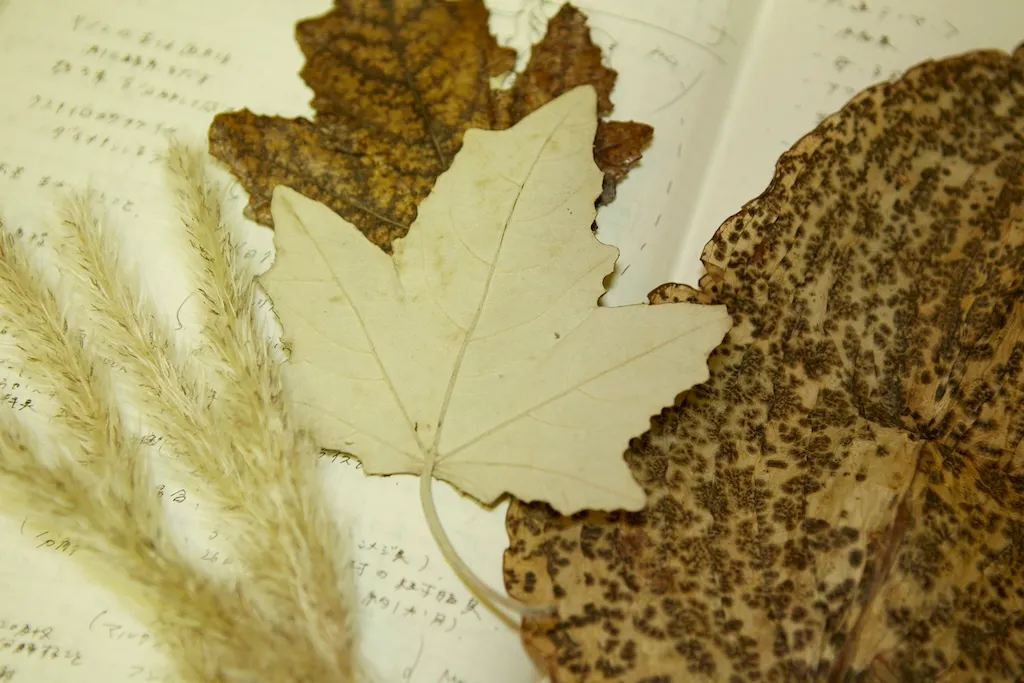

While climbing mountains as part of a nature conservation campaign, Mr. Izawa became captivated by the mushrooms he encountered. He bought an illustrated book and learned that mushrooms, as fungi, decompose dead trees, fallen leaves, animal carcasses, and excrement, returning these materials to the soil. These nutrients fertilize the soil, promoting plant growth, which animals then consume, completing the cycle of life.

Izawa

Thanks to fungi, the carcasses and excrement of animals and plants are broken down and returned to the soil, giving rise to new life. When I heard about the campaign against human waste treatment plants, I saw a connection with the work of fungi. That made me think, ‘What can I do to help?

Drawing from his experience, knowledge, and living environment, Mr. Izawa decided to immerse himself in the natural environment, becoming an active participant in the cycle, just as animals, plants, and fungi do. He has been defecating in the forest on his private property daily for about 15 years, only using a conventional toilet a few times.

By visiting the forest, digging up the excrement buried in the soil, and examining the decomposition process of his own waste, Mr. Izawa has gained profound insights into the cycles of nature.

Izawa

I always thought fungi were the main decomposers of feces, but when I started investigating and observing the process, I realized many other organisms are involved, and the process varies greatly. It’s not just mushrooms and fungi; insects and animals also play a crucial role. Every time I go into the forest, I’m reminded of nature’s incredible diversity.

As he spoke, he described the actual decomposition process in detail.

Izawa

When feces decomposes in the ground, it goes through two stages. The first stage is anaerobic decomposition, which occurs without oxygen and is carried out by intestinal bacteria. The second stage is aerobic decomposition, where fungi like molds and mushrooms break it down using oxygen.

Mr. Izawa himself has delved into the decomposition process of feces from various living creatures as part of his ongoing research. Through this lifelong endeavor, he claims to have gained numerous insights.

Izawa

When I began my digging research in 2007, it took a whole month for the feces to decompose. However, last year, it only took half that time. Over the span of 15 years of burying feces, the microorganisms enriched themselves with abundant nutrients, leading to improved soil health and strength. During a recent digging research expedition last fall with explorer Yoshiharu Sekino, we stumbled upon an area where decomposition seemed unusually slow, despite almost two months passing since the excretion. Upon closer examination, we realized that the day before I deposited this particular excrement, I had been suffering from a cold and had been on antibiotics.

Mr. Izawa suspects that the antibiotics may have hindered the fungi’s decomposition process. However, upon subsequent inspection after some time had passed, he found that even this excrement had eventually decomposed. Remarkably, even dioxin, a toxin known for its resistance to decomposition, is broken down by fungi like shiitake and maitake. Such is the potent decomposition power of fungi. On another occasion, a rare fungus was discovered in the mountains on Mr. Izawa’s private property.

Izawa

When the fungus researcher Yosuke Degawa visited, he stumbled upon the Linderina fungus in the soil he had been scouring. He had been studying an unidentified fungus species found in the intestines of cave crickets known as Rhaphidophoridae, hoping to uncover insights into fungal evolution. Linderina exhibited properties strikingly similar to those of the unidentified fungus. Consequently, he had been tirelessly searching for Linderina, which had previously only been sighted four times worldwide. If he couldn’t find it, he was prepared to pay a hefty sum to obtain one from a specialty company. Much to my surprise, it was found in my forest. Subsequent research by Mr. Degawa revealed that this forest boasted three times the soil biota richness of the neighboring primary forest.

The Key to Connecting “End” and “Beginning” Lies in Excretion

Mr. Izawa remains dedicated to a method of connecting with nature and circulation. Excretion, in essence, serves as the link between the end and the beginning, between life and life. In simpler terms, it is intricately tied to the concept of death.

Izawa

A corpse and feces share a similarity. Both are typically viewed with aversion, yet they are essentially comprised of the same deceased organic matter. But what if we perceive them differently? They both play a crucial role in passing life onto the next creature. Their demise does not mark the end of the story.

Just as eating and excreting are interlinked, something discarded by one being, having fulfilled its purpose, may be essential to another. Only by bridging the “end” and the “beginning” can the cycle of life be sustained.

Contemplating death at the culmination of life opens the door to a new beginning. This concept lies at the heart of cyclic existence, serving as the key to the intertwined activities of all living organisms.

Masana Izawa

Born in 1950, Masana’s disillusionment with humanity led him to drop out of high school and embrace a reclusive lifestyle. In 1970, he embarked on a mission to preserve nature. Eventually transitioning to photography, specializing in fungi and cryptogamic plants since 1975. In 2006, he identified himself as a fecal ecologist, advocating for a harmonious coexistence between humans and nature through lectures and writings.

Photo: Shigeta Kobayashi

Let’s Share!

The story of the cycle of life that begins with "excrement."

Share your Monthly JP pavilion and circulate your thoughts.

Related Articles

01/03

Exploring More Than 1 Kilograms of Microorganisms in the Human Intestine: A Symbiotic Relationship

Mr. Umezaki continues his research on microorganisms. The reality of the situation is “full of unknowns,” he says.

Read more

02/03

Revolve Around Microorganisms: Life, Earth, and Us

How is this world composed and how should we humans behave? The question spreads everywhere starting from microorganisms.

Read more